I promised I’d share extra treats and resources to help you with accessing more information and support for your health and fitness. These are those resources.

Mobility and Stability

Pre-made Meal Delivery

Internal Health

Fitness and Nutrition Information

These guys are best-in-class physical therapists for soft tissue mobility and stability. I’ve been in and out of hospital systems over years dealing with soft tissue injuries, mobility and stability challenges, and I’ve never encountered or even heard of a better solution than MyoDetox.

Full-body treatments for mobility and stability that combine hands-on therapy with corrective exercises, focusing on diagnosing the body, providing treatment to reduce pain, and improving movement. They help clients restore balance, decrease tension, reduce pain, align posture, increase range of motion, and build strength.

To get $45 (20%) off your first MyoDetox session, there is a discount code posted on the Instagram account for Don’t Hack Your Body at this link.

The book highlights that you may wish to use a meal delivery service to outsource all your food prep, or to have a healthy, ready-made meal in reserve if you need it in a pinch, to help introduce you to what a healthy meal might look like, or for many other reasons. I’ve tested dozens of meal prep services with varying degrees of success. The one I like the most and use daily is MegaFit Meals.

If you want to give it a try, you can use this discount code for 10% off your order: ADAMV10

All their ingredients (except salmon) are sourced from the US, and they don’t use additives, GMO's or preservatives. They use grass-fed beef and free-range chicken. Their customer service is great, delivery options are sound and they continually improve themselves. Their pricing is reasonable and, most importantly for me personally, you can customize meals to get your macronutrients down to the gram.

You may wish to go beyond the pure fundamentals of nutrition and exercise and get a full body diagnosis to understand what’s going on inside you. These are individuals and organizations I trust personally to handle this for me, and I recommend them highly.

Comprehensive, whole-body lab testing with personalized insights from top doctors to help individuals manage and improve their health. Includes blood panels and toxin screens.

Longevity, health optimization and wellness centers that give access to the latest in medicine and aesthetics for a healthier, longer life. Includes blood panels and toxin screens, among many other interventions to optimize your health.

There is a high volume of information about nutrition and fitness out there. Some sources are not so great. The ones I list here are great sources rich with data and experience, and who are passionate about these topics and about helping people be a better version of themselves. Many are free. The principles of nutrition and exercise don’t change much, but our understanding of them does evolve. You can stick to the principles I outlined in the book and only those principles for your entire life. It still helps to check in with the greats every now and again. Here are a few who have helped me and who I would highly recommend:

Dr. Aaron Horschig at squatuniversity.com. There is no one better for stability and mobility. Kelly Starrett is the only one I’ve found who’s in the same league.

Kelly Starrett at thereadystate.com. If Horschig doesn’t have the answer, Kelly probably will. And vice-versa.

Christopher Sommer at gymnasticbodies.com. Coach Sommer is a great resource on mobility, stability and functional strength, particularly exercises.

Ben Bergeron at his gym or his podcast. Bergeron focuses primarily on Crossfit athletes, and I don’t encourage you to pursue Crossfit casually. Only if you wish to play it as a sport. However, he is a wealth of knowledge. Particularly around your mental game.

Mark Rippetoe at Starting Strength. Rippetoe is one of the gurus of strength training. He is an expert on the fundamentals if you want to do a deep dive on power lifting technique.

Louie Simmons at Westside Barbell. Simmons is another strength training guru. He is a great resource for advanced powerlifting training methods for advanced competitors.

For exercise science:

Videos of exercises. A quick Google search will get you anything you need to know. I like the ones on this Crossfit page because they are no-nonsense and have great angles and key pointers.

Gokhale Method. Esther Gokhale is a wonderful resource for posture.

Dr. Terry Wahls. Her TED talk Minding Your Mitochondria changed how I think about food and gives dramatic form to the fact that food is medicine.

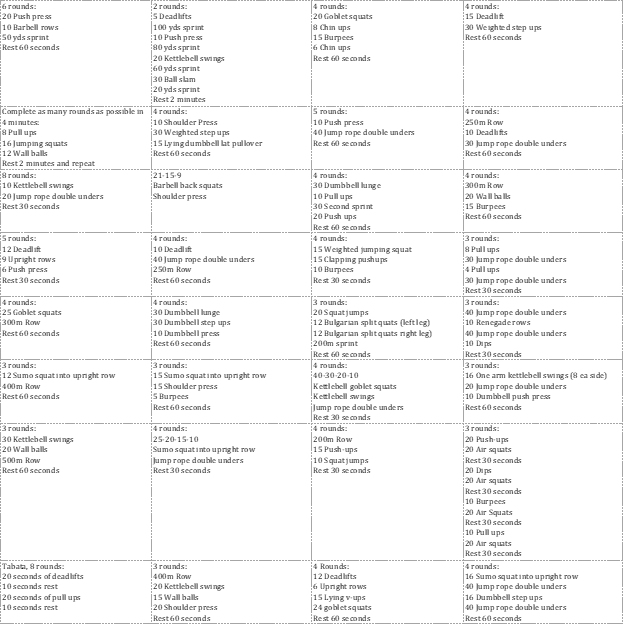

HIIT (MetCon) Examples

HIIT (MetCon) Examples for a “Moderate” Program

In the book, I noted you can create a Moderate exercise program (the “better” program in the “good-better-best” classification). This could be an abbreviated program that consists of just one or two resistance exercises and a MetCon. Or you can create a program that is just a MetCon.

In these abbreviated programs, you need to train all the muscle groups in your whole body in each exercise session—upper and lower. Thus, your MetCons should also target your full body rather than just upper or lower. You would do this workout 3 times per week. Here I’ve shared examples of MetCons that target the upper and lower body together (rather than separate upper and lower) that you can use to build this type of program.

“Minimum” Exercise Program Design

The following are sample MetCons that I’ve done over the years and incorporated in my standard programming cycle, with a focus on upper body versus lower body. These are also in the book.

3-day per Week Exercise Program

Sample Nutrition Plans

Alternative Exercise Programs

In the book, I noted that you can create a Minimum exercise program (the “good” program in the “good-better-best” classification). The workout can consist of traditional resistance exercises. Alternatively, you could do just a MetCon. You could simply warm up and then complete one of the full-body MetCons above. You could do this 3-4 times per week.

Alternatively, you can design a program that is comprised of low resistance, high repetition exercises. For example, you can try 4 sets of 20-30 reps per exercise with 30 seconds rest between sets, and 4-8 sets per muscle group per day. With this type of program, you can take advantage of isolation movements that can tax muscles at a higher level with lower weight (for example one-legged squats, Bulgarian split squats, elevated one legged squats, weighted chin-ups or pullups, dumbbell curls, etc.). You would apply the same principle of progressive overload as in any program and increase resistance whenever possible.

If you don’t have access to any resistance equipment at all, then you can rely on plyometrics and bodyweight exercises. In this case, you’d also rely heavily on MetCons. You can follow the general programming outline we used earlier and just substitute exercises and add sets as needed.

As yet another alternative, you could complete a full body circuit of Tabata push-ups, Tabata Bulgarian split squats, Tabata pull-ups, and Tabata air squats, or anything else you can do based on what you have available. That would give you two upper body and two lower body exercises. It takes 15-20 minutes and then you’re on your way. You can introduce progressive overload to these, as well, by adding more repetitions or adding resistance.

A 3-day per week exercise program can be just as effective as a 4-day per week program. The following is a 3-day program that uses the same principles as the 4-day program we built together in the book.

The following are two examples of my personal nutritional plan. The first plan puts me in a slight energy surplus. I gain muscle and roughly maintain fat with this program, with a slight net gain. I’m an advanced practitioner so I can gain about 1.0 lbs of muscle every 7-8 weeks or so, and I lose fat at a slower pace than that. That is slowwwwww. But I’m consistent, and so are my results. It’s pretty much on autopilot so it’s easy, doesn’t require a lot of time and attention, and I can sprinkle in cheat meals a few times per week to be social with friends and enjoy life. I typically stay between 9.5%-10.5% body fat at all times.

This is only meant as a sample framework so you can see one detailed example of how the principles you learned in the book can be applied. This isn’t meant for you to mimic because, as you learned in the book, it might not work for you. Also, there are plenty of flaws with this and readers could have a field day picking nits. One of the principles of this book is you need to be able to live and enjoy your life and that one attribute of your optimal nutrition plan is that it’s one you’ll consistently follow. After years of tweaks and ongoing changes that change with my lifestyle demands, this consistently works for me.

I also an example nutrition program I’ve used in the past to be in energy deficit to lose fat at a slightly faster pace while still building muscle. Note that the total calories are more than 10-20% less than what my maintenance would be. They’re about 25% lower. The fact that I use this specific program and it works for me is unique to my body. Also, I wouldn’t switch immediately to the lower calorie volume overnight. I’d eliminate calories over a few weeks to arrive at this lower amount. And I’ve only used this after having fun testing some other program for research if my body fat percentage climbed (for example 11-12%+). I recommend you start in about a 10-15% total calorie deficit, test, and recalibrate until you find what works best for you.

In the book I noted that there are alternative programs I’ve tried and like to help mix things up from my standard week-to-week program. One of my favorites is called the 20-squat program. There are a few variations of this program. This is the one I’ve used and like.

One note: this is not for beginners, de-conditioned or older practitioners. Don’t do it. If you are intermediate or advanced, and if you have perfected your squat with a coach or through years of careful training, you might dig it. That is especially true if you identify yourself as a ‘hard-gainer’, because it requires that you are in caloric surplus while completing it. It can be a “plateau-blaster”.

The concept is simple. You squat every 3-4 days, and you do only one big set of 20 reps. Every day you squat, you add 5 lbs. to the weight you squatted last time. This requires what are called “breathing squats”. The first day of the program you begin with a weight you can comfortably squat for 10-12 repetitions. After you’ve completed those reps, you pause with the bar still on your shoulders and take a few breaths. You then complete another repetition. You repeat that until you reach 20 repetitions. It takes your leg muscles well into failure. Complete the rest of the exercises in the program as normal exercises. It’s a unique and very difficult program. But it can be effective. Do not continue this program for more than one 6 week cycle. Otherwise you will almost certainly over-tax your body. Also, a cycle like this isn’t meant to be done more than one or at most two times per year. The program was designed with just resistance exercises and no Metcons. I included a variation with limited MetCons to ensure aerobic capacity doesn’t fall off a cliff during the cycle and to allow access to the hormonal hypertrophy pathway. It can be done with or without them. Since this program isn’t for beginners, experienced practitioners should be able to adapt to the additional work of the MetCons without difficulty. I’ve included a list of MetCons specifically designed for this program here.

As discussed in the book, you may wish to build a resistance exercise program that prioritizes the hormonal growth hypertrophy pathway rather than the mechanical tension hypertrophy pathway. If so, the goal is to accumulate a high level of lactate with each set. In that case, you want your exercise selection, resistance level, volume of sets and reps, and rest period between sets to all support that. The following is a sample exercise program for the hormonal pathway. The goal is to target each muscle group with 1-2 exercises each day. The resistance level will be relatively low, around 50-65% of your 1RM. It is a 3-day program that trains the entire body each day. Due to the relatively lower volume and targeting of the hormonal hypertrophy pathway, recovery is quicker such that each muscle group can be trained with 48 hours of rest. Remember, unlike the mechanical tension pathway, these sets are meant to be taken to failure. The first 4-5 sets might not get you there, but the last few will. In that vein, please note that this workout is a scorcher. It is difficult to complete and you will be very fatigued. Beginners may struggle with this workout. If you’re a beginner and still wish to try it, just ensure the resistance level you select is on the lower side of things. The first 4-5 sets of each exercise may not feel challenging. But just wait until you get to sets 6-8. Things heat up real fast.

The concept for the program is structured like a MetCon – similar in concept to the Tabata protocol, actually. Each exercise 8 rounds of 30 seconds of work followed by 30 seconds of rest for a total of 4 minutes of work. The tempo of the reps is moderate, roughly 2 seconds negative and 1 second positive with slight transitional pauses in between for smooth, clean reps. If done correctly each round should have about 8 reps. The key is to ensure the 30 seconds of work is continuous with no breaks and the rest is no longer than 30 seconds so the lactate in the muscles doesn’t have time to clear (thus, the hormonal hypertrophy pathway). Some of the exercises are single leg movements that require 30 seconds of work on one leg followed immediately by 30 seconds of work on the other leg and then 30 seconds of rest. Keep in mind the mechanical tension will be less than the other programs discussed because the resistance is lower. Keep an eye out for opportunities to increase the weight to get progressive overload, even though it will come even less frequently. And keep in mind you won’t be able to increase reps to get progressive overload, only resistance, because the rep count is fixed. That is yet another reason I recommend you are at least an intermediate practitioner to attempt this program.

If you don’t like this format but still want to stay in the hormonal pathway hypertrophy domain, try doing 2 exercises for each muscle group, and for each exercise complete 4 sets of 25 reps per set with 30-40 seconds rest between each set.

Guidance for the Four Major Strength Exercises

In the book, I shared that there are critical components of major compound exercises that many demonstrations omit. I want to point out some concepts in written word that can be difficult to see when you’re watching a video. The following are detailed descriptions of how to execute the squat and other key compound exercises

Squat

To squat, position your body underneath the bar. The bar should rest along your trapezius muscles, behind your shoulders and above your shoulder blades. For reference, this is a high bar squat, as opposed to a low bar squat. Both are acceptable variations and a great leg workout. Lowering the bar on your back will change the angle of your hips as you descend and activate slightly different muscles in different ways, and it won’t allow you as much depth. I recommend the high bar squat unless you have a specific body mechanic that prevents it. The high bar squat will allow you to perfect this critical movement and identify and remedy any mobility hurdles. While the bar is positioned here, avoid contracting your traps and pulling the bar upwards. The bar will rest snugly in there, but that’s it. You’ll see why in a moment. Grip the bar with your hands far enough apart that your forearms make roughly a 90 degree angle with the floor or slightly wider. Your wrists should be neutral (straight, not forward or back).

Start with your feet about shoulder width apart. There is no correct or incorrect width in foot positioning. We are all anatomically different, and that can influence the optimal width for you. You may also have mobility limitations (though you should be actively addressing those to correct them). I recommend you begin at shoulder width and recalibrate over time as needed as you learn what stance allows you to access full squat depth while maintaining the remaining components of form I review here.

Drive your chest forward and up while keeping your back straight and rigid. At the same time, activate all of the muscles along your spine and your lats. This (along with your abdominals) is absolutely critical to maintaining stability during this lift, so you can perform it correctly and get the hypertrophy benefits. If you find your squat isn’t improving, it may be because you’re not getting this form correctly. Do this by driving your elbows down to the floor and in toward your hips, hard. Don’t pinch your scapula muscles together and flare out your shoulder blades. Your elbows are going down and in, not back. If helpful, you can think about pinning together your lats and triceps. If this is difficult for you, whether it’s difficult exerting control over these muscles or the muscles are weak and deconditioned, then start practicing your banded W raises in your mobility program and get those stabilizer muscles active and strong.

Hinge your hip back (which will lean you slightly forward) with your glutes fully activated (like trying to pinch a credit card between your butt cheeks by using the outside of your butt checks to do it). You’re not squeezing your cheeks together and thus driving your hips forward. It’s the opposite. In fact, your knees will bend a little and your hips will slide back slightly like you’re getting ready to sit down in a chair. This will activate your hips fully. Doing calf-banded squats in your mobility work will help you perfect this.

Now your chest is up, your back and lats are active, your hips are active, and your glutes are active. Press yourself into the bar, lifting it up out of the rack. Take one step back. Double check to ensure everything you just stabilized and activated didn’t come undone during the step back. Re-engage.

Your weight should be evenly distributed over the middle of the foot. The feet form a tripod with the heel, the base of the big toe (ball of the foot) and base of the pinky toe. The weight should be right in the middle. Some trainers may tell you to think about driving through your heels. That’s okay if it helps you mentally since you may find yourself leaning forward and find your weight shifting to the balls of your feet. But your weight and drive should really be from the middle of the foot. Angle your feet either straight forward or slightly out to the side, no more than about 30 degrees.

Engage your abdominals, hard. This will generate the stability and a lot of the power for your lift. If your abs aren’t engaged and stable, your lower back will try to step in. You can actually feel this happening, because you will begin to lean forward a bit and hinge forward from your lower back. One trick to help with this in addition to keeping your abdominals fully engaged is what’s known as mentally putting your back into the bar. It’s sort of like pre-empting the forward hinge. Mentally, you can think of it like using your abs to stabilize you as you hinge backward and push your upper back against the bar. This intense abdominal engagement is why your abs get such a crazy workout when squatting. If you do this correctly, your abs will feel taxed and depleted. They may even be a bottleneck and you may notice them losing strength in the late reps before your legs do. They’ll get stronger as you progress.

Take a breath. You will hold this breath during the entire descent and let it out at the top of the ascent. Think about making yourself fat. Your stomach will expand out with your breath held in. Also, take note, this means you will be actively engaging your abdominals with a belly full of air, which may be new territory for a lot of people who are used to having abs at their highest engagement while air is out of the stomach.

Open your hips and descend. While squeezing your glutes the entire time, drive your knees out with the knees tracking over your toes. You’ll know if your hips are too far out if you rock toward the outside of your foot and the ball of your foot under your big toe comes up off the ground a bit. You’ll know if your hips are too far in if you rock toward the inside of your foot and the base of your pinky toe comes up off the ground a bit. As you continue to descend, your knees will eventually drive forward past your toes. If this is difficult for you, then focus some stability work on ankle mobility and hip mobility. You will notice profound changes that can dramatically improve your hypertrophy as you improve this lift and get all the benefits of it free from mobility and stability constraints. Descend until your thighs are parallel to the ground. You can go deeper if you’d like. But it isn’t necessary.

The bar should stay over the middle of your foot during the entire squat, both the descent and ascent. If you ever video yourself squatting, see if the bar goes straight up and down in a line, or if there’s any curvature to it. It should move in a straight line every time.

To ascend, drive your hips up while activating the glutes using the ole’ credit card pinch. To really understand how to optimize this part of the squat, get really good at calf-banded squats in your stability program. You should be warming up for your squats with those. The band will be pulling your knees together and force you to really resist and push against the band as you descend and ascend. It will teach your brain how to properly activate and stabilize your hips and glutes and your leg muscles drive you up and out of the bottom position.

Deadlift

The Romanian Deadlift is the exercise that I prioritize in the program we built together and in my own program, but I’m going to focus on the deadlift for the tutorial. The deadlift is slightly more difficult to execute. And once you get the deadlift down, it’s fairly straightforward to transition that knowledge and ability to the Romanian Deadlift.

The first thing to say about the deadlift is that it is primarily a glutes and hamstrings exercise. If you find yourself really shredding your lower back (or mid or upper back) during this lift, that’s a red flag that there’s a problem with your form.

Deadlift technique has a lot of overlap with squat technique. Your feet should be roughly shoulder width apart, and can also vary depending on your individual anatomy. You will also use the same tripod concept for balance with your feet. You will point your toes out slightly, no more than about 30 degrees. Your knees will drive outward and track over your toes. You will breathe in, get fat, and engage your abdominals hard for stability during the lift. You’ll engage the muscles along your spine for control and stability.

First, address the bar. Walk up to the bar so there are only a couple inches between your shins and the bar. Stand shoulder width apart and angle your toes. Bend to grip the bar at a width that is roughly shoulder width so your hands are outside your hips. Squat down, sitting between your legs so your thighs are parallel to the floor. Align and activate your shoulders by bringing them back (away from your chest) and down (toward your hips). Engage the muscles along your spine for stability. Engage your lats. Your lats should be fully activated and in full flex the entire duration of the lift. They will allow you to keep the bar close to your body during the lift and resist rounding your back. If it helps, mentally think about trying to bend the bar. Your arms should be fully extended. They won’t contract. You’re not pulling with your arms. Think of them like hooks that are fixed in place. They should be rigid and your triceps should be fully activated. You are now in position.

Squeeze the bar and create tension before you begin the lift. Pull the bar against the top of the inside ring of the weights and take out any slack in both the weights and in your arms. Begin your ascent. Mentally, don’t think of lifting the bar up. Think of holding onto the bar and using it to push your feet through the floor. Also, don’t think of going up and down. Think of going forward and backward with your hips as the hinge. On the ascent, you are driving your hips forward. As you do this, that forward driving motion will cause your hamstrings to straighten and your lower back to move into an upright position. Ensure you keep the bar extremely close to your body the entire time, so that you’re nearly dragging the bar along your shins and thighs.

Once you have reached to top of the lift begin the descent. The descent is just the ascent in reverse. Keep the same rigidity in your back, lat, and tricep muscles for stability. Put your mind into your glute and hamstring muscles for the descent. Don’t let the weight fall. Resist gravity and drive your hips backwards while bending your knees. Keep the bar close to your body. The final part of the descent is almost a squat as the bar settles back to the floor. Make sure to learn and maintain control during the eccentric (descent) part of this lift. You may feel the urge to let gravity do all the work and just let a controlled drop take place. Our purpose here is hypertrophy, not lifting for strength and power. So don’t cut out half of the exercise.

Your back shouldn’t be rounded. It should be straight and rigid. Note that there may be some slight rounding to your back. You may have even seen professional power lifters with meaningful rounding. There are circumstances under which that can be okay for extremely experienced practitioners because they know how to stay stable and rigid even with some rounding in their back and only drive the movement with the muscles that are meant to be dedicated to the lift. For our purposes of developing hypertrophy and learning this movement, there should be minimal, if any, rounding.

Shoulder Press (dumbbell)

I give strong preference to dumbbell press over barbell press to avoid the risk of impingement and other injury. However, both versions of the press are excellent. To establish rigidity and stability to prepare for the movement, focus on your back muscles, your triceps, your abdominals, and your hips/glutes. Use the same activation and tension principles as the squat to activate all of the muscles along your spine and your lats. Drive your elbows down to the floor and in toward your hips. Don’t pinch your scapula muscles together and flare out your shoulder blades. Similar to the squat, if this is difficult for you, whether it’s difficult exerting control over these muscles or the muscles are weak and deconditioned, start practicing your banded W raises in your mobility program and get those stabilizer muscles active and strong. It might seem contradictory to drive your elbows down to the floor since they are going to move upward to execute the pressing movement. But that is the magic of this lift. The shoulder press is effectively a banded W raise without the lateral component of the movement. If you perfect the banded W raise, you’ll have a perfect shoulder press. This will also help prevent you from shrugging during the movement. You know how to activate and stabilize your abdominals from the squats. To activate the hips and glutes, get tension in your legs by mentally turning your heels into the ground like corkscrews. With a slight bend in your knees, activate your glutes and hips with the ole credit card in the butt cheeks technique you know and love. You are prepared to make the movement.

Ensure your shoulders are in a neutral position, down and back. This should already be their position if you have properly activated your back and lats. Grip the dumbbells with palms facing out. Your elbows should be down and slightly in front of your shoulders, not flared out to the side. Extend your arms straight up, ensuring your elbows don’t flare out at any point during the movement and your shoulders don’t shrug upward. Press the weights up until your arms are fully extended. Ensure the weight is directly above your shoulders and not edging forward or backward either in front or behind your head. The descent should follow the same track as the ascent.

Bench Press (dumbbell)

Just like with the shoulder press, I give strong preference to dumbbell bench press over barbell bench press to avoid the risk of impingement and other injury. However, both versions of the bench press are excellent. Lie down on the bench and get your muscles active and organized. Start by anchoring your upper back into the bench. Your upper back and your butt should both have contact with the bench. The rest of your back doesn’t need to be flush up against the bench and if it arches, that’s okay. The key points of contact are your upper back and butt.

Activate the muscles along your spine, bringing your shoulders back and down. You don’t’ want to hyper extend your shoulder blades, but your scapula muscles should be rigid and active keeping you stable throughout the entire lift. This is done in a similar way as the squat and almost the same way as the shoulder press. Activate your lats and lock them in. Your lats will be key in creating control during the descent and drive during the ascent. Your lats do meaningful work during bench press.

Anchor your shoulders, locking them down and back. There will be immense temptation to allow your shoulders to roll or drive forward during the pressing motion. Resist this with everything you’ve got, primarily by keeping those muscles along your back active and rigid and your lats flexed and active during the lift. If helpful, mentally think about the bar being in a fixed position and you are driving your upper back down through the bench.

Anchor your feet and create rigidity in your hips. Plant your feet away from your hips so you can use them to help create drive.

Grip the dumbbells with your hands slightly wider than shoulder width apart. Keep your elbows underneath the dumbbells, making sure your elbows don’t flare out (i.e. for a 90 degree angle with your lats), which puts immense pressure on the rotator cuff.

Begin the descent. Continue to keep your elbows under the dumbbells. Your elbows should make roughly a 45 degree angle with your lats. Your back muscles should be rigid, and your lat muscles should be actively resisting the weight. Lower the dumbbells until they reach the level of your sternum (just below the bottom of your pectoral muscles). Note that the path of the dumbbells wasn’t straight up and down, but that it formed more of a “J” motion. This will be the same path the dumbbells will track back up on the ascent. If you are using a bar, it should make light contact with your sternum. If you’re using dumbbells, they should lower to that same level.

Begin the ascent. Keep your butt on the bench and push your hips back with your legs by pushing through your heels. While pressing the bar up, you should be driving your shoulders down toward your hips and back into the bench, as if you’re using the dumbbells to push your upper back through the bench. You should feel an intense flexing of your pectoral muscles through the ascent until you reach the top of the motion.

One of the best warm-up and stability exercises you can perform for the bench press is a banded bench press. Get a lightweight band and wrap it around your wrists at shoulder width apart as if you were bench pressing but without any weight. Instead, push your wrists laterally against the tension of the band. With that tension in place for the entire duration of the movement, complete the repetition as if you would a normal bench press. If you do this and banded W raises as warm up before your bench press, you’ll set up your body for clean, stable movement.